In his letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett looks back on his investment mistakes. Some bad moves occurred early on. Others he committed when he was old enough to know better. His purchase of Dexter Shoe, for instance. By the 1990s, most New Englanders could have told him the region's shoe industry was in hospice care.

Perhaps that misjudgment related to his earlier faith in New England's vanishing textile industry, which first moved south, then overseas. But without that faith, the name Berkshire Hathaway never would had gotten a second wind.

Here, from 1964, is an ad from the "old" Berkshire Hathaway.

Saturday, February 28, 2015

Friday, February 27, 2015

They Lived Long and Prospered

Leonard Nimoy as Mr. Spock voiced the words: "Live long and prosper." He will be missed.

So will Irving Kahn, who lived those words.

Wall Street's oldest active professional investor, Kahn made his first stock trade in the summer of 1929 and became a disciple of Benjamin Graham. Until last fall he was still reporting for work three days a week at his midtown office. Kahn died at age 109.

Related post: Good Advice From a 108-Year-Old Investor.

So will Irving Kahn, who lived those words.

Wall Street's oldest active professional investor, Kahn made his first stock trade in the summer of 1929 and became a disciple of Benjamin Graham. Until last fall he was still reporting for work three days a week at his midtown office. Kahn died at age 109.

Related post: Good Advice From a 108-Year-Old Investor.

Thursday, February 26, 2015

Wealth Management for the Deluxe Lifestyle

Jim Gust called my attention to the premiere issue of the redesigned New York Times Magazine, thick with ads. Four million dollar condos. Watches with unmentionable prices. And a surprising number of marketing messages from wealth managers catering to the upper crust.

BNY Mellon boasts of a 97% client retention rate. First Republic spotlights one of its entrepreneur banking customers. Bessemer Trust expresses willingness to manage new wealth alongside old wealth. Glenmede, despite having dropped "Trust" from its logo, features its status as a privately-held trust company.

For readers of the magazine who are not yet really rich, Fidelity, Fisher, Schwab and Merrill Edge also offer wealth-management help.

Back in Mad Men days, nobody would have expected to see those ads in the Sunday Times magazine. A quick look at the comparable magazine section for February, 1965 reveals that ads for women's fashion and home furnishings dominated. Men were offered stereo record players.

Ads for investment services and products? Back then they were found in the Sunday business pages. Mutual funds were a hot topic, as shown at right.

Ads for investment services and products? Back then they were found in the Sunday business pages. Mutual funds were a hot topic, as shown at right.

One reason for the migration of investment ads to the magazine section of the Sunday NY Times was the need to reach women. Equally important, wealth managers to the truly wealthy wanted to burnish their upper-crust image: "We manage family fortunes for the sort of people who own multimillion-dollar condos and buy expensive watches without looking at the price tag."

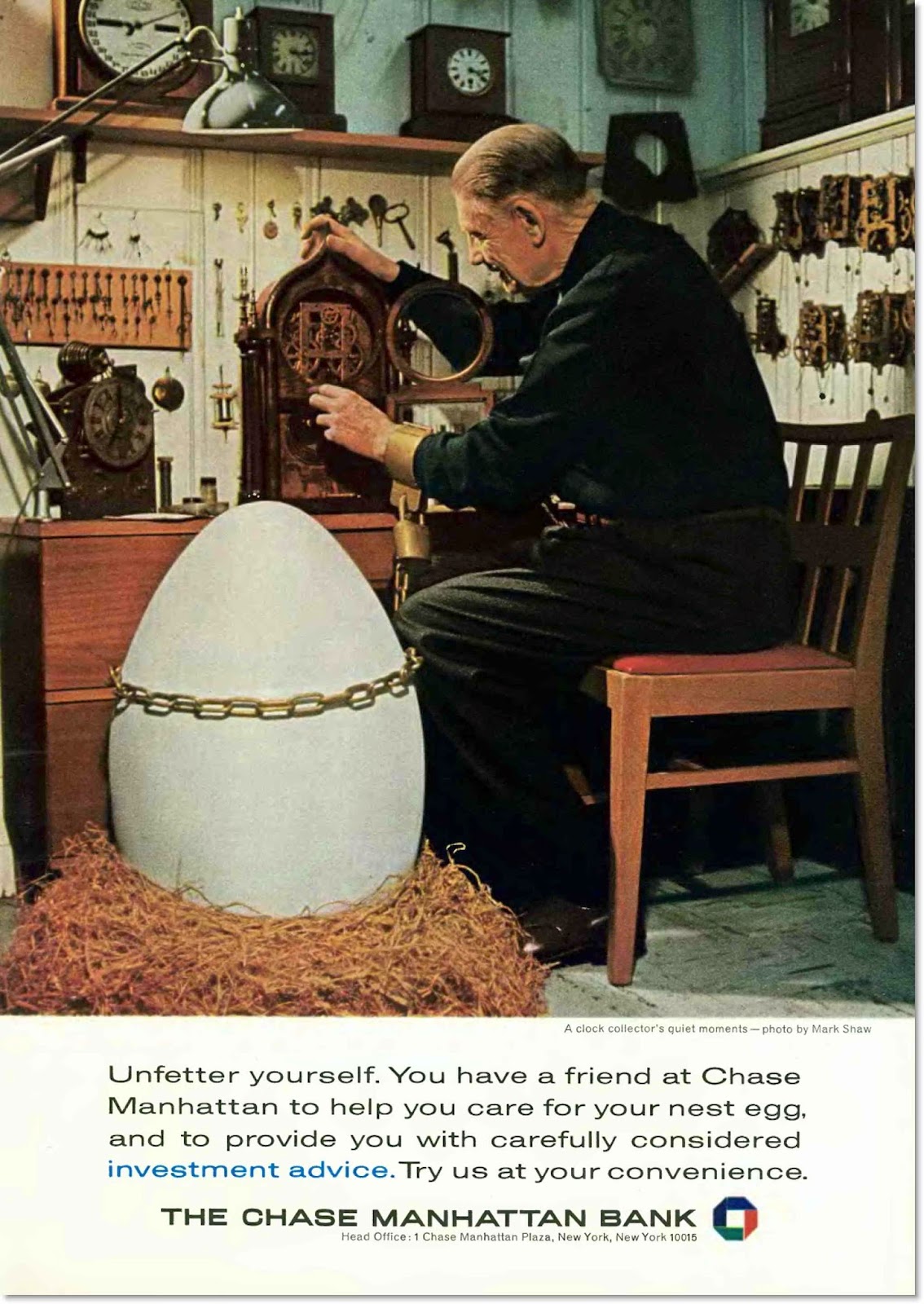

Neither of those motivations is new. As we've shown you from time to time, back in the 1960s Chase Manhattan and U.S. Trust regularly advertised in The New Yorker. On that magazine's pages their messages mingled with ads from purveyors of women's fashions and suppliers of all manner of upscale merchandise. And, of course, Chase ads could run in full color.

Here's a nest egg ad from the winter of 1964-65, portraying a clock collector. Does he seem a bit stolid for the Swinging Sixties?

BNY Mellon boasts of a 97% client retention rate. First Republic spotlights one of its entrepreneur banking customers. Bessemer Trust expresses willingness to manage new wealth alongside old wealth. Glenmede, despite having dropped "Trust" from its logo, features its status as a privately-held trust company.

For readers of the magazine who are not yet really rich, Fidelity, Fisher, Schwab and Merrill Edge also offer wealth-management help.

Back in Mad Men days, nobody would have expected to see those ads in the Sunday Times magazine. A quick look at the comparable magazine section for February, 1965 reveals that ads for women's fashion and home furnishings dominated. Men were offered stereo record players.

Ads for investment services and products? Back then they were found in the Sunday business pages. Mutual funds were a hot topic, as shown at right.

Ads for investment services and products? Back then they were found in the Sunday business pages. Mutual funds were a hot topic, as shown at right.One reason for the migration of investment ads to the magazine section of the Sunday NY Times was the need to reach women. Equally important, wealth managers to the truly wealthy wanted to burnish their upper-crust image: "We manage family fortunes for the sort of people who own multimillion-dollar condos and buy expensive watches without looking at the price tag."

Neither of those motivations is new. As we've shown you from time to time, back in the 1960s Chase Manhattan and U.S. Trust regularly advertised in The New Yorker. On that magazine's pages their messages mingled with ads from purveyors of women's fashions and suppliers of all manner of upscale merchandise. And, of course, Chase ads could run in full color.

Here's a nest egg ad from the winter of 1964-65, portraying a clock collector. Does he seem a bit stolid for the Swinging Sixties?

Thursday, February 12, 2015

Another item for the estate planning checklist

Designate a "legacy contact" for your Facebook account.

The person won't know about the special status until you die, unless you tell him or her beforehand.

The person won't know about the special status until you die, unless you tell him or her beforehand.

Monday, February 09, 2015

In Defense of Investment Advisers

After collecting their one percent annual fee, most investment advisers are doomed to underperform the market. More likely than not, an amateur investor could do better – just invest in index funds, sit back, be patient and get richer.

Investment advisers, not to mention brokers, appear redundant. – useless or worse. William Berstein sees them as a threat to financial health and happiness:

Polite or not, the critics ignore a key reality: Most people cannot invest sensibly on their own. At best, perhaps a third are willing and able to put their money into a few diversified, low-cost funds and stay the course.

Others need somebody to hold their hands and discourage them from buying high, selling low. Some are reluctant investors. In begone times they would have been contented savers, putting their money into 3.5-percent savings accounts and 6-percent CDs. Nowadays they must seek investment help or grow poorer.

In short, most people with money to invest still need advisers. What’s different is the adviser’s mission. Instead of tilting with windmills and seeking to beat the market, the adviser’s aim should be to produce better results for the investor than the investor would achieve on his or her own.

And that goal should be often achievable;. The bar is set surprisingly low. From 1994 through 2013, the S&P 500 produced an annualized return of 9 percent. The average stock fund investor earned 5 percent.

Some estimates suggest the gap in returns is even greater after accounting for all fees and other expenses.

Does a 20 percent increase in investment performance sound worthwhile? By controlling expenses with ETFs and limiting fruitless trading, an adviser could achieve that impressive improvement merely by increasing the investor’s annualized return from 5 percent to 6 percent. A low-cost, exceptionally patient adviser might achieve 7 percent – a 40 percent improvement!

Helping clients beat the average investor rather than beat the market doesn’t sound glamorous. It won’t earn advisers enough to acquire a beach house in Malibu. But it is doable.

Like politics, investing is the art of the possible.

Investment advisers, not to mention brokers, appear redundant. – useless or worse. William Berstein sees them as a threat to financial health and happiness:

As an investor, you must recognize the monsters that populate the financial industry. *** … most “finance professionals” don’t even realize that they’re moral cripples, since in order to function they’ve had to tell themselves a story about how they’re really helping their customers.Some critics are less polite.

Polite or not, the critics ignore a key reality: Most people cannot invest sensibly on their own. At best, perhaps a third are willing and able to put their money into a few diversified, low-cost funds and stay the course.

Others need somebody to hold their hands and discourage them from buying high, selling low. Some are reluctant investors. In begone times they would have been contented savers, putting their money into 3.5-percent savings accounts and 6-percent CDs. Nowadays they must seek investment help or grow poorer.

In short, most people with money to invest still need advisers. What’s different is the adviser’s mission. Instead of tilting with windmills and seeking to beat the market, the adviser’s aim should be to produce better results for the investor than the investor would achieve on his or her own.

And that goal should be often achievable;. The bar is set surprisingly low. From 1994 through 2013, the S&P 500 produced an annualized return of 9 percent. The average stock fund investor earned 5 percent.

Some estimates suggest the gap in returns is even greater after accounting for all fees and other expenses.

Does a 20 percent increase in investment performance sound worthwhile? By controlling expenses with ETFs and limiting fruitless trading, an adviser could achieve that impressive improvement merely by increasing the investor’s annualized return from 5 percent to 6 percent. A low-cost, exceptionally patient adviser might achieve 7 percent – a 40 percent improvement!

Helping clients beat the average investor rather than beat the market doesn’t sound glamorous. It won’t earn advisers enough to acquire a beach house in Malibu. But it is doable.

Like politics, investing is the art of the possible.

Sunday, February 08, 2015

Nigeria Forever!

From today's email. Or so I conjecture.

I hereby would want to bring to you the good news about your long awaiting fund, The Federal Ministry of Finance, Nigeria, and the Banking industry here in Nigeria in-conjecture with Central Bank Of Nigeria held meeting in Abuja regarding all foreign payment.

Saturday, February 07, 2015

Tips For Donors and Charities

Paul Sullivan's Wealth Matters column reveals an unusual corner of philanthropy: helping companies with ill-gotten gains give away their tainted funds.

Lesson for donors: Giving money away usefully can be hard work. Wealthy individuals who fund a new dorm for their alma mater or a new wing for the local hospital have it easy. Donors who have to come up with their own ideas do not. Giving away money effectively, Steve Jobs believed, was more difficult than making it.

Lesson for charitable recipients: Donors expect feedback. Most charities who received portions of the ill-gotten gains failed to report on how they used the money. The minority who did won additional grants.

Lesson for donors: Giving money away usefully can be hard work. Wealthy individuals who fund a new dorm for their alma mater or a new wing for the local hospital have it easy. Donors who have to come up with their own ideas do not. Giving away money effectively, Steve Jobs believed, was more difficult than making it.

Lesson for charitable recipients: Donors expect feedback. Most charities who received portions of the ill-gotten gains failed to report on how they used the money. The minority who did won additional grants.

Friday, February 06, 2015

Paul Gauguin, From Wealth Manager to Destitute Artist

At age 23, Paul Gauguin started a successful career as a Parisian stockbroker. He fell in with the arty set, including Pissarro and Degas.

If Gauguin didn't invent the midlife crisis, surely he perfected it. In his late 30's he abandoned his job, his family and middle-class life to become an artist. Economically, it was downhill all the way. Only after Gauguin's death in 1903, sick and destitute in Tahiti, did his paintings become prized.

Fast forward to 2015. One of Gauguin's works, painted during his first stay in Tahiti, just changed hands at a price higher than any other painting is known to have fetched: nearly $300 million!

What do you suppose the wealth manager turned artist would have made of that news?

If Gauguin didn't invent the midlife crisis, surely he perfected it. In his late 30's he abandoned his job, his family and middle-class life to become an artist. Economically, it was downhill all the way. Only after Gauguin's death in 1903, sick and destitute in Tahiti, did his paintings become prized.

Fast forward to 2015. One of Gauguin's works, painted during his first stay in Tahiti, just changed hands at a price higher than any other painting is known to have fetched: nearly $300 million!

What do you suppose the wealth manager turned artist would have made of that news?

|

| This Gauguin sold for a record price of almost $300 million. |

Thursday, February 05, 2015

About those tax "cost" estimates

A client recently had a question about the current issue of Estate Planning Report:

JCT does not explain their methodology or assumptions for specific line items. Frankly, the numbers make no sense to me. I take it that they assumed the restoration was for one year only, that the charitable rollover would be repealed for years 2 – 10, so the later years cost far less. But then why don’t they cost zero? How do they lose $19 million in year 10 for donations made in year 1?

But even worse, let’s unpack the numbers a bit to see what they mean. By definition, the donations are coming from those over 70 1/2 and can’t exceed $100,000. For the sake of round numbers, let’s assume that their tax rate is 23.9%. To lose $239 million in one year, you have to assume that $1 billion would have otherwise been included in the income of these retirees, presumably as required minimum distributions. To get to that number you need to have 10,000 retirees each make a maximum $100,000 charitable rollover contribution—that seems absurdly high to me. Alternatively, 100,000 taxpayers could donate $10,000 each, but that still seems equally unlikely. I doubt that there are that many IRAs large enough to sustain such large donations, especially just in the last two weeks of the tax year when such rollovers were allowed. Remember, only those over age 70 1/2 are even eligible. Presumably only those with IRAs worth $1 million or more would consider such a large donation, and GAO reported there are only about 600,000 IRAs that large in the country.

But still worse than that, they also must have assumed that the affected seniors would not have exercised their right to simply take the RMD, give it to charity, and claim the deduction in the usual way! That seems like the most unlikely assumption of all. That’s why I concluded the paragraph with the notion that the JCT seems to be assuming that charitable gifts won’t be made at all in the absence of this provision.

Am I missing something?

I’m not sure what the dollar amounts mean in the second paragraph?? Tax cost the first year is $239 million and the ten-year cost is only $384 million.These are the numbers that the Joint Committee on Taxation submitted as the lost revenue for allowing the tax-free rollover of funds from an IRA to a charity. Here’s my source. You may recall that in December Congress reinstated the tax-free charitable rollover for a single year, and it has now expired again. They scored it as losing $239 million in the first year and from $12 to $19 million every year after that. It’s line A8 of the table.

JCT does not explain their methodology or assumptions for specific line items. Frankly, the numbers make no sense to me. I take it that they assumed the restoration was for one year only, that the charitable rollover would be repealed for years 2 – 10, so the later years cost far less. But then why don’t they cost zero? How do they lose $19 million in year 10 for donations made in year 1?

But even worse, let’s unpack the numbers a bit to see what they mean. By definition, the donations are coming from those over 70 1/2 and can’t exceed $100,000. For the sake of round numbers, let’s assume that their tax rate is 23.9%. To lose $239 million in one year, you have to assume that $1 billion would have otherwise been included in the income of these retirees, presumably as required minimum distributions. To get to that number you need to have 10,000 retirees each make a maximum $100,000 charitable rollover contribution—that seems absurdly high to me. Alternatively, 100,000 taxpayers could donate $10,000 each, but that still seems equally unlikely. I doubt that there are that many IRAs large enough to sustain such large donations, especially just in the last two weeks of the tax year when such rollovers were allowed. Remember, only those over age 70 1/2 are even eligible. Presumably only those with IRAs worth $1 million or more would consider such a large donation, and GAO reported there are only about 600,000 IRAs that large in the country.

But still worse than that, they also must have assumed that the affected seniors would not have exercised their right to simply take the RMD, give it to charity, and claim the deduction in the usual way! That seems like the most unlikely assumption of all. That’s why I concluded the paragraph with the notion that the JCT seems to be assuming that charitable gifts won’t be made at all in the absence of this provision.

Am I missing something?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)