Bought cider doughnuts at the farmers market last weekend – six bucks for a half dozen. A dollar a doughnut.

"Dollars to doughnuts" was how our forebears described a virtually sure bet. At the dawn of the 20th century a loaf of bread cost a nickel, so doughnuts must have sold for a penny or less. After more than a century of inflation, my doughnuts cost 100 times as much.

Since the Great Recession, inflation has been so muted that the Federal Reserve has wished for more. We sometimes forget how even low inflation keeps dinging the value of a dollar. Savers suffer, and so do investors who may assume they're reaping profits.

Say you bought stock at $100 in 2008 and now sell at $120. A modest profit? Not after paying federal income tax on your capital gain. Thanks to a decade of "low inflation," you need to net more than $117 just to break even.

From time to time Congress has toyed ineffectually with the idea of indexing capital gains to inflation. Could the Treasury do the job for them, perhaps by issuing a regulation redefining capital gain?

Anything's possible, but we'd guess it's a dimes to doughnuts bet.

Showing posts with label Inflation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Inflation. Show all posts

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

Sunday, October 01, 2017

When Deficits Meant Tax Hikes, Not Cuts

From half a century ago, August, 1967, comes this Life magazine editorial.

"The case for a tax increase…is a persuasive one." Although the U.S. had run deficits in nine of the previous 10 years, "the sheer size of the one now confronting the nation is fearsome."

Current deficits run bigger, in terms of GDP, than they did half a century ago. Can you imagine our president or any member of Congress proposing a tax increase?

Life also mentions the need to restrain high inflation? How high? Three percent, a level today's fiscal engineers seek to promote.

You're right, Dorothy. We're not in the 20th century any more.

Thursday, April 10, 2014

Life and Taxes in Mad Men Days

Mad Men starts its last season Sunday. Heralding the event is a poster by a real Mad Man, Milton Glaser, still active at 84.

Times Machine, the new, improved portal to New York Times archives going all the way back to the 1800's, offers subscribers an easy way to relive Mad Men days. I'm struck by how the ads tell you as much about the era as the articles.

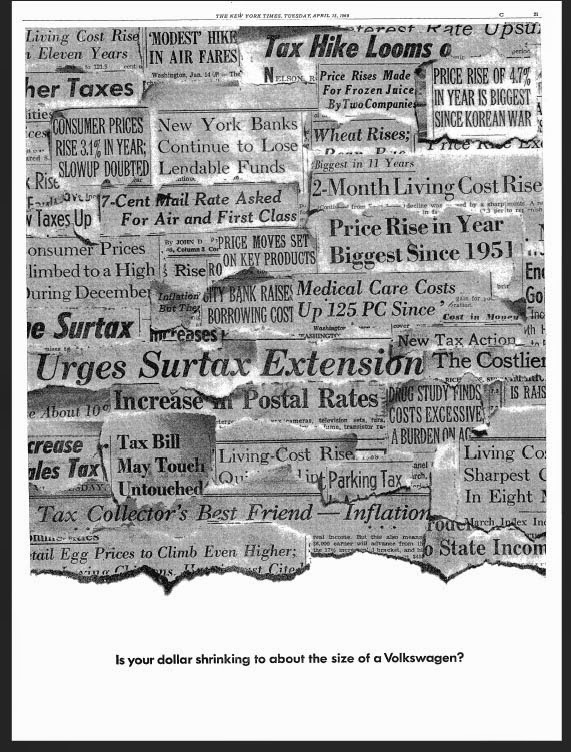

Here, for instance, is an offbeat Volkswagen ad from tax time, 1969.

The Consumer Price Index had increased by less than 2% a year from 1958 through 1965, so the 4% rise in 1968 was cause for alarm. These days, believers in growth through inflation might welcome it.

Times Machine, the new, improved portal to New York Times archives going all the way back to the 1800's, offers subscribers an easy way to relive Mad Men days. I'm struck by how the ads tell you as much about the era as the articles.

Here, for instance, is an offbeat Volkswagen ad from tax time, 1969.

The Consumer Price Index had increased by less than 2% a year from 1958 through 1965, so the 4% rise in 1968 was cause for alarm. These days, believers in growth through inflation might welcome it.

Wednesday, December 04, 2013

Inflation Watch (Theater Edition)

Broadway had its best Thanksgiving week ever at the box office, reports The New York Times.

Top ticket prices at selected musicals:

Top ticket prices at selected musicals:

The Lion King: $197.50

Wicked: $300

The Book of Mormon: $477

A little over half a century ago, a ticket to the theater in London cost $3.50. According to this 1961 British Travel ad, a mere $100 could buy you a whole week in the U.K.

Guess that's why they call them The Good Old Days.

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

Was Nobody Wealthy Before 1980?

Thanks to John Mauldin for sharing Dylan Grice's The Language of Inflation. Brice enlivens his critique of the Great Credit Inflation with examples of changing word usage as charted by Google's Ngram Viewer.

The term "wealth management," for instance, surged in the 1990s. Before that, memories of the Great Depression made people wary of flaunting their wealth. Besides, it wasn't good form.

Today, "wealth management" often has little to do with real wealth or real management. Grice illustrates with a story:

The term "wealth management," for instance, surged in the 1990s. Before that, memories of the Great Depression made people wary of flaunting their wealth. Besides, it wasn't good form.

Today, "wealth management" often has little to do with real wealth or real management. Grice illustrates with a story:

[W]e attended a lunch recently in which one … “wealth manager” was promoting his services to those around the table. An Italian gentleman claimed to be relieved to have finally found someone who could help him. “At last!” He gasped after the banker’s pitch, “I could really use some help managing my family’s wealth. We own vineyards and a processing plant in Italy, some land and a broiler farm in Spain, some real estate scattered around Europe and the Americas... We are fortunate indeed to have such wealth, but managing it all is increasingly challenging. Can you help?”

The poor banker looked forlorn. Of course, he didn’t mean that kind of wealth, the old-fashioned, productive kind of stuff. He meant the modern, papery, electronic kind. The stuff that blinks at you all day from a screen.Grice offers food for thought, although I can't get my head around his reference to"no inflation over the last thirty years." Do I pay more than twice as much today because everything is more than twice as good?

Tuesday, July 09, 2013

Millionaires Aren’t What They Used To Be

Reporting on the latest Spectrem survey of millionaires, The Guardian places people with $1 million among the "super-rich." The Telegraph describes them as "mega rich."

Are Americans with investable assets of $1 million really extremely rich? Or, as noted here recently, are they actually too poor to afford a comfortable retirement?

Most truly rich people will tell you that $1 million is small change. To most other people, especially those wrestling with high credit-card balances and student loans, $1 million still sounds like a vast fortune.

For sure, $1 million isn't what it used to be.

To live like a millionaire lived in 1987, you today need $2 million.

To live like a millionaire lived in 1976, you need $4 million.

To live like the millionaire of 1959, you need $8 million.

To live like the millionaire of 1945, you need $13 million.

And to live like the millionaire of 1935, you need $17 million.

Are Americans with investable assets of $1 million really extremely rich? Or, as noted here recently, are they actually too poor to afford a comfortable retirement?

Most truly rich people will tell you that $1 million is small change. To most other people, especially those wrestling with high credit-card balances and student loans, $1 million still sounds like a vast fortune.

For sure, $1 million isn't what it used to be.

To live like a millionaire lived in 1987, you today need $2 million.

To live like a millionaire lived in 1976, you need $4 million.

To live like the millionaire of 1959, you need $8 million.

To live like the millionaire of 1945, you need $13 million.

And to live like the millionaire of 1935, you need $17 million.

Wednesday, March 03, 2010

Happy Tenth Anniversary?

"It's time to celebrate -- or perhaps mourn -- the 10th anniversary of one of the epic financial events of our time: the peak of the great stock market bubble in March 2000."

In his Washington Post column, Allan Sloan recalls just how good the good times were:

The chart of the DJIA below is revealing for two reasons: market swings are kept in proportion thanks to a log scale, and you can compare the nominal average with the real (inflation-adjusted) version. Props to Terence Corcoran for including the chart with this Financial Post comment.

The bad news: Corcoran suggests that the stock market's "lost decade" could be the first leg of another major market downturn, like 1966-82. We haven't actually slumped that much yet, kept aloft for a while by the real-estate and financial bubbles. But the first phase of the previous slump didn't seem too bad, either: Though "story stocks" might tank, market gurus opined circa 1970, nothing could ever go wrong with Xerox, Avon and the other famous large-cap names that made up the "Nifty Fifty."

The bad news: Corcoran suggests that the stock market's "lost decade" could be the first leg of another major market downturn, like 1966-82. We haven't actually slumped that much yet, kept aloft for a while by the real-estate and financial bubbles. But the first phase of the previous slump didn't seem too bad, either: Though "story stocks" might tank, market gurus opined circa 1970, nothing could ever go wrong with Xerox, Avon and the other famous large-cap names that made up the "Nifty Fifty."

Well, almost nothing.

The good news: If we are in the midst of an eighteen or twenty year slump, we're at least half way through it. For the rest of way, Boomers (the employed ones) may be able to invest at relatively favorable levels. By the time they retire or semi-retire in 2018 or 2020 and the market turns up, they should feel pretty good financially.

Meantime, they better heed Sloan's last bit of advice: "… take care of yourself by living below your means, doing your homework, and being careful and skeptical."

Related post: The Next Stock Market Boom.

In his Washington Post column, Allan Sloan recalls just how good the good times were:

For a generation -- August 1982 through March 2000 -- U.S. stocks had their greatest run ever. The S&P 500 returned almost 20 percent a year, compounded, including reinvested dividends. You doubled your money in less than four years, quadrupled it in a little more than seven. It's the kind of thing people could get used to, and over a generation, many did.The aftermath? Ten years of volatility and market trauma.

The chart of the DJIA below is revealing for two reasons: market swings are kept in proportion thanks to a log scale, and you can compare the nominal average with the real (inflation-adjusted) version. Props to Terence Corcoran for including the chart with this Financial Post comment.

The bad news: Corcoran suggests that the stock market's "lost decade" could be the first leg of another major market downturn, like 1966-82. We haven't actually slumped that much yet, kept aloft for a while by the real-estate and financial bubbles. But the first phase of the previous slump didn't seem too bad, either: Though "story stocks" might tank, market gurus opined circa 1970, nothing could ever go wrong with Xerox, Avon and the other famous large-cap names that made up the "Nifty Fifty."

The bad news: Corcoran suggests that the stock market's "lost decade" could be the first leg of another major market downturn, like 1966-82. We haven't actually slumped that much yet, kept aloft for a while by the real-estate and financial bubbles. But the first phase of the previous slump didn't seem too bad, either: Though "story stocks" might tank, market gurus opined circa 1970, nothing could ever go wrong with Xerox, Avon and the other famous large-cap names that made up the "Nifty Fifty."Well, almost nothing.

The good news: If we are in the midst of an eighteen or twenty year slump, we're at least half way through it. For the rest of way, Boomers (the employed ones) may be able to invest at relatively favorable levels. By the time they retire or semi-retire in 2018 or 2020 and the market turns up, they should feel pretty good financially.

Meantime, they better heed Sloan's last bit of advice: "… take care of yourself by living below your means, doing your homework, and being careful and skeptical."

Related post: The Next Stock Market Boom.

Monday, October 26, 2009

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Another Unintended Consequence

Back in the 1970s, Uncle Sam learned to love inflation. Holders of Treasury bonds and other creditors could be paid off on the cheap, with depreciated dollars. Remarkably, Congress decided to stop stiffing retirees in the same fashion. Social Security benefits were indexed to inflation. As a result, those who retired 10 or 15 years ago receive roughly the same real benefit – with the same spending power – now as they did then.

Guess what? Most retirees don't care a fig about such notions as "real benefits" and "maintaining purchasing power." They believe their benefits increase every year. And they like it that way.

Result, an unexpected new political crisis. No inflation (as measured by the Consumer Price Index) means no dollar increase for 2010. Or, as The Washington Post puts it, Stagnant Consumer Prices Prevent Social Security Benefit Increases.

Uncle Sam is expected to apologize for those stagnant consumer prices by sending each retiree $250.

(Many retirees, including this one, feel the actual cost of retirement living has kept climbing over the last 12 months, but that's an argument for another day.)

Lesson for wealth managers: You may need to explain the declining purchasing power of the dollar and its consequences to more clients and prospects than you realize.

Guess what? Most retirees don't care a fig about such notions as "real benefits" and "maintaining purchasing power." They believe their benefits increase every year. And they like it that way.

Result, an unexpected new political crisis. No inflation (as measured by the Consumer Price Index) means no dollar increase for 2010. Or, as The Washington Post puts it, Stagnant Consumer Prices Prevent Social Security Benefit Increases.

Uncle Sam is expected to apologize for those stagnant consumer prices by sending each retiree $250.

(Many retirees, including this one, feel the actual cost of retirement living has kept climbing over the last 12 months, but that's an argument for another day.)

Lesson for wealth managers: You may need to explain the declining purchasing power of the dollar and its consequences to more clients and prospects than you realize.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)